Turnings

Cope Cumpston

The poster was taped on a wall in the science building hallway. A schooner leaned tall into whitecaps, sails swollen with wind against an immense blue sky. The banner above, Openings: oceanographic apprentices for the Research Vessel Westward.

Not an instant of hesitation. I copied the phone number and called later that afternoon. Application written, folded and tucked into an envelope I dug from deep in my desk drawer. Stamped and sealed. I walked down the two flights of the echoing concrete stairwell of my dorm, envelope pressed against my heart, and dropped it in the mailbox.

It was 1972, the spring of my senior year in college. “What next?” was the thrumming drumbeat – a promise and a terror. The door before me was both open and shut, like the four years at Harvard that had broken all my expectations

* * *

The path was decreed. My grandfather, “Happy Jack,” was a beloved professor at Harvard Law School, my grandmother was Radcliffe college marshall and doyenne of high-flying conversations in the deep blue velvet sofa on Hubbard Park, a cul-de-sac off Brattle Street. My mother obeyed the nod toward Radcliffe and finished in three years so she could marry my father before he shipped overseas for the last months of World War II. From my early teens, Dad would flash a grin and say, “You’re going to have the time of your life at Harvard.”

Mom had a degree in economics but never used it. She and Dad joined lock step in the sweep of their time; he finished MIT on the GI bill, got a job at Kodak and they moved to Rochester. Soon my sister Mary arrived. Two years later, according to plan, Hank. I was third and last; Mom told me I was the result of a wild party.

By then our young family had moved three times.

Dad was smart, stubborn, and defiant. If a company didn’t welcome his ideas, things began to chafe. Every three years, regular as clockwork he’d quit or be fired, and we were off to a new adventure. Mom’s job was to manage moves and children. She festered under the confinement, but oversaw a perfect household by means of an explosive and unpredictable temper. We kids lurked, anxious not to provoke the ire of the valkyrie.

When we heard Dad’s car in the driveway, it was safe to come out. He’d give a funny bark he learned in the army to announce he was home, toss his jacket on a chair, and stride into the kitchen. Reach in the refrigerator for the gleaming glass martini shaker, filled to the brim. He’d give Mom a grin and pour the two special glasses, and pull out the jar of white cocktail onions. He used a long handled ice-tea spoon to pull out three, one for each of his nightly martinis. On weekends it was usually more than two. If I was quick I’d get one onion just for me. I loved the sharp vinegary taste.

Mom would put away her apron and her rage. She’d smile and settle her perfect posture in a deep chair as Dad handed her a drink. With a grin on his face, he’d take a big swig and close his eyes to savor the liquid fire. That was the official start of The Hour of Charm, which melted any tensions until dinnertime when Mom or Dad would snipe at each other over some trivial thing and be back at their bickering. Mom would eventually storm out in tears and we each went our separate ways.

I kept tabs on the moods of the house and buried myself in a book until it was safe to come back out. I was Dad’s eager assistant, hovering at his elbow in the basement wood shop, sweeping up the fragrant sawdust that gathered by the bandsaw. He always found a task that fit my fingers. He’d guide my hand with the drill, and summon me for the drive to the lumber yard, just the two of us, for his next project.

School was easy. I skipped second grade and was the tiny kid who thrust her hand up first and was fierce when the teacher posed a question. I was certain in the lessons, eager for each new puzzle, thrilled with each new subject. I turned the lush pages of my textbooks hungrily in my room at night. At recess I was shy and awkward, hanging outside until there was a space for my timid step into the circling jump rope. When other girls turned their eyes toward boys I was years behind.

I didn’t question the plan. When it came time, Harvard said yes and just like my Dad I followed my nose. It led me to Cambridge in September 1968. And then up and over the high iron gates of Harvard Yard the night of April 9, 1969.

* * *

A man from the Sea Education Association called to schedule an interview. I summoned my best adult act, pulled a skirt from the back of the closet and made my way, butterflies roiling in my belly. Walk to the subway, buy a token, edge through the turnstile and down the steep stairs into the rumbling underground. On the train to Park Street I swayed and jolted with the carful of strangers in business clothes, each intent on some mysterious journey. This was my first foray into the world without the family script.

I found my way to the address and was shown to a corner office. A man with iron grey hair and heavy glasses looked up from the papers on his vast polished desk. He was serious in a perfect grey suit, eyes steady. He nodded toward a chair and I sat. Dad had taught me to look straight into someone’s eyes and shake hands with a firm grip. I summoned my mother’s determination as I sat, her straight back and intent smile, her certainty and charm. I was young and small, but early on I had realized my teachers held me in some kind of awe. I practiced the persona.

He liked my shiny Harvard credentials. I didn’t admit my doubts that I deserved them. Or that they meant what they promised. Neither of us mentioned that for sailing experience I had precisely none. Or scientific training. I recognized in him a New England character like my mother; we faced each other, proper and erect, betraying no uncertainty. He gazed out the window as he talked of the Westward. We conspired in the dream, that exquisite ship carving her way through the waves. “This is the seventh research trip for the Westward; the interns meet her in San Juan, go through the Panama Canal and on to the Galapagos Islands. The scientist is Peter Pritchard; he studies the nesting habits of sea turtles. He needs data from the Pacific.” I leaned forward in my chair, barely breathing, eyes wide. I described the courses I’d taken, my plans for graduate school in oceanography.

And was accepted as an intern on the Research Vessel Westward. I took a deep breath, felt the winds of destiny blowing clear the wreckage of my college years, and turned my face toward the Pacific.

* * *

I had entered Harvard as naïve and doe-eyed as they come. We Radcliffe girls had our own dorms a 15-minute walk from Harvard Yard. The “men of Harvard” outnumbered us 4 to 1. We girls were “too smart and too serious,” and ruined the grade point curves for jocks and legacy admissions. When it came to dating, the guys headed to Boston College and Pine Manor, where they knew they impressed the coeds. Our dorm parents opened their apartment for movies on Saturday night; my friend Linda and I brought a box of dried dates as our personal joke. It was a lonely place. No one counseled me, either academic or personal.

I wanted to understand what made people tick; Social Relations felt like the right major. The intro started with anthropology — the social behavior of baboons, and efforts to teach sign language to a chimp named Washo, then onto clinical psych, with experiments that surgically rotated chickens’ eyes and tested how their nerves and behavior adapted. When we got to people the categories were N-Ach, need for achievement and N-Pow, need for power. The right fit for Harvard. B. F. Skinner was a campus figure who probed the portents of behaviorism; there were whispered stories about him putting his own children in a “Skinner Box,” for controlled stimuli and response. I took careful notes in cavernous lecture halls from each male eminence, who stood remote and inaccessible.

* * *

It was the dusty end-of-summer when Mom dropped me off in Cambridge for my freshman year. Things were not usual although I didn’t know it yet. The summer of love in Haight Ashbury had migrated east, bringing drugs, sex, rock and roll, and the politics of protest. Walking to classes I passed the hippies who hung out on the Cambridge Common, in clouds of what I learned was marijuana smoke. Huge puppets from the Bread and Puppet theatre acted out political morality plays, protesting Vietnam and American imperialism. I began to realize that my parents were on the conservative side of the political spectrum, although they never explained what it was all about. In the dorm, I was surrounded by the radical women of SDS, the Students for a Democratic Society. I’d walk to the bathroom amid tense conversations and strategy sessions. They plotted the overthrow of the Harvard establishment. We shared a phone, a rotary landline with a long twisting cord that reached from room to room. Our calls had odd echoes and delays; the SDSers were certain the line was tapped. I was outside their world but breathed in their anger and urgency.

* * *

My sea adventure required a $2000 payment; that I had to earn before we shipped out in January. An old couple rented me an attic room in their worn house near Radcliffe. They supplied me with an antique hotplate and space in the refrigerator, and I gloried in life on my own. I was thrilled with my own creaking cot and threadbare brown spread, a cupboard of a closet and a window framing a huge maple. It was what I needed, nothing more, nothing less. Good training for life at sea. Come January my ration of fresh water would be five cups a day, and my private space a narrow bunk with some shelves and a dim lamp.

After graduation I kept my night job from college; at 6 I’d walk to the converted garage that connected to the neat brick home of The Harvard Crimson. Under the sharp eye of our production manager Pat, I helped typeset and put together each daily issue. I’d sit at my keyboard waiting for the night editor to rush in with a sheaf of pages typed on yellow foolscap, the latest story I loved the teamwork, the urgency, the clacking and chirring machines that spit out long strips of typeset galleys to be cut in columns and pasted up on pages. My fingers danced faster and faster across the keys as the hours approached the deadline. When the last bit was in place Pat gathered the pages, turned off the lights and left for the printer. I walked the quiet streets to my attic eyrie, warm to know that my work would soon churn through a huge printing press, be bundled and delivered for dawn delivery on doorsteps throughout Cambridge. To the president and my grandparents.

By day I doubled as a temporary secretary. This would be my journey, on my terms. My big brother bought me a Pentax camera; he wanted me to photograph this adventure with the best equipment. I saved up for what I needed for three months at sea: a Swiss army knife with every blade including a marlinspike for repairing sails, clothing to protect against the equatorial sun, sleeping bag for my bunk and camping on islands on the Galapagos. Dad gave me the heavy canvas duffle bag he’d used in the war. My sister made a journal for me, bound with brown netting over cardboard, just like an old captain’s sea log.

* * *

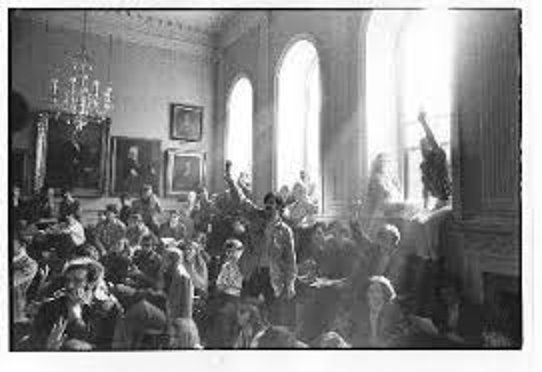

There was nothing normal about my class in Soc Rel 101 on the morning of April 8. SDS had taken over University Hall – dragged 8 deans down the stairs and out the door. They’d gotten no response from the administration in response to their demands that the campus expel ROTC and end its investments in war, so they took over the administration building and locked themselves inside. I had no opinion about their political demands, but I had to know what was going on inside Harvard Yard.

The gates of Harvard Yard had been locked, but I knew that whatever was going on inside was more educational than anything I’d hear in a lecture hall. I knew the real thing when I saw it. I gulped a quick dinner and rushed alone to Harvard Yard. A tall friend boosted me high so I could struggle up and over the tall black spikes. I saw the chapel doors open wide, with an intent group gathering inside. They motioned me in; they were preparing for confrontation. The hours dragged on, the chapel grew dark. I lay on hard red cushions and somehow slept.

At 5 am voices burst in, “The pigs are here!” I stumbled through the grey dawn and joined the frightened group on the steps of University Hall. We linked arms as a meager barricade against we knew not what. A fleet of silver buses, sleek and ominous as barracudas, glided silent through the opened gates and spewed out some 400 state troopers in baby blue uniforms and riot gear. They were quiet, eyes masked behind visors. On a sudden command they raised batons and rushed in, clubbing through us like so many gnats. A guy shielded me with his arms as the sticks struck hard in all directions. We fled onto the grass, whitefaced and stunned, as the police broke through the doors and streamed inside. It was a chaos of thuds on skulls, curses and screams, bodies falling to the floor. Uniforms emerged dragging protesters streaming with blood. They shoved some 200 onto buses and drove out.

I stood shaking in the pale dawn, unutterably alone. The faces around me were drawn, some dripping blood, eyes dark in the sudden silence. There was nothing to do but walk back to my dorm. Campus shut down with opposing sides declaring their positions: those who supported the occupiers and those who denounced the rebellion. Many faculty were heartbroken that the administration had called for violence against its own students. I called my parents, not knowing what to say. Dad burst in loud and clear — students had no business tearing apart their school. It was right that they were arrested. He didn’t leave space for me to say anything. His final word: “It would have made as much sense to protest the name of Soldiers Field Road.” He was a distant, curt voice on the phone, then silence.

The promises of Harvard were trampled in the dirt.

I had stumbled through the end of that year; final exams were cancelled. My sophomore year was worse. We all pretended things were back to normal until May 4 when the National Guard shot and killed four protesters on the Kent State campus. Protests waved across the campus and beyond. One night I ran to join a massing mob, and heard a terse voice barking orders over a bullhorn. I asked the guy next to me what he said; he shrugged his shoulders. “The cops say disperse or we’ll shoot.” The mob jostled and shots exploded. Never before had I run for my life. I heard a thud and the guy next to me stumbled to the ground. Pounding footsteps, rigid terror. A block away I stopped, gasping for breath. It turned out the police had fired buckshot. Was that a “warning”? To me it was war.

Those years are grey in my memory. I wanted to take a year off but my father shook his head – “if you leave, it’s likely you’ll never go back. A degree from Harvard will open doors for the rest of your life.”

On some blind whim I took a class in marine biology. The professor glowed with his subject, pacing before the class, his voice rich with excitement. Entirely unlike what I knew from Social Relations. I took a crazy leap and dove into the physics of atmospheres and oceans, the ecology of coral reefs. I had enough credits in Soc Rel to graduate, but my heart was leaping in ocean waves. All my life I had watched my dad meet frustration with defiance, quit jobs and find a new dream. I seized mine. I’d take the science I needed after I graduated to go on and study oceanography. I crumpled the pages of the family script.

Better yet – I’d go to sea. That poster beckoned and I was on my way.

* * *

In January 1973 I found my way to an American naval base in Puerto Rico where the Westward was docked. I had made it through my first solo airplane flight, lugging the heavy duffel bag. A few shaky steps across a tilting plank took me on deck, and a sudden roll pitched me off balance. I left land seeking a grounding more certain than what I’d experienced at Harvard.

The Westward was even more imposing in person than her photographs. A lean, elegant white-hulled ship with sleek lines, dark polished teak decks and trim. Every detail compact and necessary. The heavy canvas sails, 13 of them, were wrapped tight around the two masts and boom, patiently awaiting release. A network of rigging rose some 80 feet to the crow’s nest. I vowed to make that climb as soon as allowed, up the rough hemp ropes into total solitude and total immersion in blueness, sea and sky. The right place for dreamers with good balance. We were many on that ship.

A few crew members on deck passed cartons of canned food to waiting arms below. The sun that much closer to the equator and the sea air were thick and smothering, so close after Christmas at home in Vermont. The smells were sharp and strange – tar? Something rotting? Barrels lashed to metal struts emitted a briny smell with more than a hint of decay. Diesel. Salt, saturating everything. I stepped into the dark through the hatch, down the teak ladder into what was called the main saloon. Paul the steward pointed to the curtained bunk that was mine. It held a narrow mattress and a shelf for my things. I pushed my heavy bag inside, took a deep breath, and entered my new life.

In the first weeks we learned the discipline of sea voyages. Eighteen apprentices were assigned to A, B, and C watches. We scrubbed decks and heads and attended to the ship around the clock. We took turns at the binnacle, the compass that directed the course set by the gorgeous teak wheel that controlled the rudder. We learned the mechanics and the urgency of raising and lowering sails in all weather, leaning our full weight against the winches that held the sheets – the ropes — heavy canvas whipping in the wind wild enough to knock a person overboard. Almost always when the captain called to trim a sail a huge guy five years younger would leap over me to seize the line. I wasn’t sorry to stand aside. Off-duty I quickly found favorite places to sit and study the ocean waves. It was remarkable how on a ship that was just 126 feet from bow to bumpkin, 26 people could disappear into a favorite solitary space. Weather permitting, mine was a perch on the sail wound around the bowsprit, rising and lunging with the waves, watching for the dolphins who loved to taunt and splash their human companions. I’d write long hours in my journal, finding words to recount the marvel of being at sea.

Liam Keller

Liam Keller currently lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba. He is a part-time law student and works at a pet grooming and boarding facility, writing in his spare time. He began writing during his undergraduate studies in Toronto, pursuing it more seriously over the past year, during the pandemic.